Have you ever tried to access public information about Providence on the web? Due to the recent, and new, requirement that residents reapply for their homestead tax exemption in Providence, I decided to poke around the Providence webpage to see what kind of public information on property was available online.

I was greeted with an IT nightmare1.

The system was clearly a third-party developed or purchased front end designed for searching public records on property and sold to municipalities throughout the country by winning contracts through the RFP process. It’s also clearly no longer supported (or supported poorly), outdated, and running on hardware that’s probably about as powerful as an 8-year-old desktop computer. The system crawls, when it’s not completely still, and provides no means of easy export that I can find.

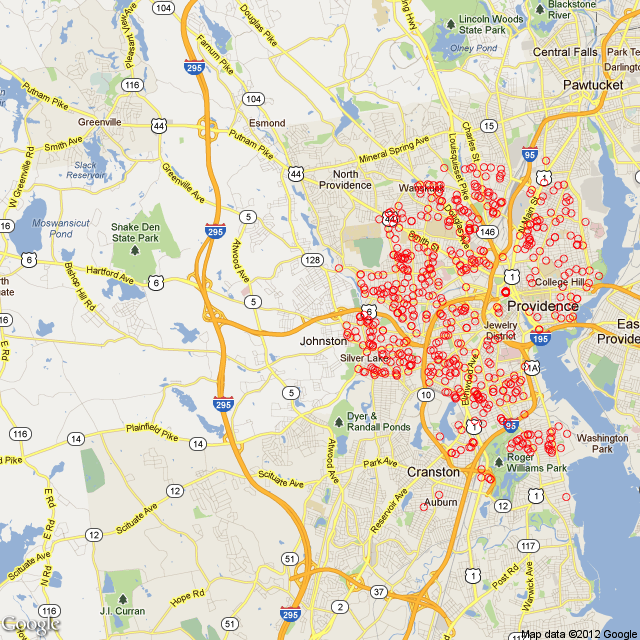

This was really disappointing to me. In an earlier post, I began to look at some simple data available on the Providence Journal’s webpage about recent sales. I was hoping to use an API (and in the worst case, a massive data dump) to get access to information about the assessed value of recently sold properties and to play around a bit with various heat maps and see what patterns are revealed. Even if there were some way to get access to the data, the application is so poor I definitely do not have the patience required.

This is a real shame, because one of the great things about data on property is that it is all public information. This means that the data could be shared widely to creative policy wonks, data geeks, and CS nerds looking for a weekend project. There are now two cities2in the US that are employing a new kind of CIO– the Chief Innovation Officer– whose role is to connect government resources, be they employees, data, or infrastructure, with folks who can do something new, exciting, and useful for city residents.

Developers designed one application in San Francisco to reduce the “notoriously cumbersome hurdles for starting a new business.”3Does anyone happen to know of another city, perhaps without the rich, entrepreneurial technology and science economy it lusts for, that is not known as an easy place to set up shop? Hint.

When Brown University has an excellent computer science department made up of undergrads who work on side projects like developing an online course catalog since the Brown purchased system sucks, it’s hard not to conclude that there are latent geek talents just waiting to be tapped. And it’s not just Brown that could be engaged. What about Swipely, the newest tech startup from entrepreneur Angus Davis, a Rhode Island native who is very active in local government and developing Providence. An exciting. fledging technology company with young, smart folks who do application development with huge swaths of data every day is an excellent source of the kind of talent Providence needs. Why hasn’t someone approached Swipely about a charity opportunity– take all non-essential staff off their current projects, give them a break from the deadlines and typical day, and get them working furiously for a week on rolling out something awesome and useful for city residents. It would reinvigorate young coders and greatly benefit the city.

Heck, something as simple as getting in and teaching government employees how to spin up instances of Amazon EC2 4 so they can migrate off self-managed, slow servers for non-secure information would be huge. Imagine this, plus rolling an API for critical municipal data sets. There would be a rich environment for hobbyists, students, and professionals alike to spark some creative ways to understand and interact with Providence.

Another example, assuming it’s legal, how long do you think it would take a smart developer, dedicated solely to one task, to roll a system that would cross-reference Providence landowners with the DMV registration database so that myself and other residents didn’t have to trek out documentation to City Hall to avoid a 50% tax hike?

Providence is not San Francisco, but there are many talented developers and data scientists who are passionate enough about the city to donate their time and expertise. Honestly, for many of these folks there are real personal benefits, even without appealing to some sentiment of civic duty. So let’s open up our data, our infrastructure, and our employees. Let’s encourage folks from outside of government to inject excitement and new skills for current government IT employees and analysts.

It’s time for Providence’s own “Summer of Code”.