My life will be defined by the last decade. How could it not be? In 2010 I graduated from a fifth-year master’s program and entered the workforce full time for the first time. Elsa and I started dating in 2010 as well. I began both my career and family life with the decade.

These were the first ten years of my adult life.

Author’s Note: Each image is a thumbnail. Please click through the galleries– there’s quite a bit of this story being told in their titles and captions.

2010

2011

In 2011, I bought a condo, Elsa and I got a dog, Gracie, and moved in together.

2012

In 2012, I quit my first job and started a fellowship with like-minded education data professionals. For the first time, I had a meaningful professional network. I left my first job for all the right reasons. I had learned a lot but could see no opportunities for growth or change on the horizon. My boss would hold his job for at least another 7 and maybe 10 years. I wasn’t sure I’d want his job anyway. I was trusted and respected, and already had opportunities to work in almost all parts of the organization and choose the projects I wanted to contribute to. I had a great job, but it would be that same job forever. Meanwhile, three years out from finishing my undergraduate degree and a couple of years out from graduate school, I saw many of my classmates switching jobs into new and exciting opportunities that they came across through the professional networks they were building. I was building no network— we had no money for professional development, a complete travel ban unless required as a part of a grant, and I worked in a state agency in a small state. It a was hard decision— I did enjoy my job, but I needed to leave to grow.

2013

In 2013, I struggled professionally. I left a supportive, if limited, environment and found myself unready for the rigors of independence. I had two bosses in two different organizations, both of whom saw me as self-motivated and self-reliant, My work was largely long term projects. I went from working in a cubicle on many small projects always on a team to working alone in a quiet office or from home if I chose to do so. While I had a professional community through my fellowship, in many ways, my daily professional life was quiet and lonely. I made steady progress but had a hard time building day to day motivation. I had long thought I might get a Ph.D., but it became horrifyingly clear that managing an independent, long term research project was draining, not invigorating. I enjoyed teaching and being a part of an academic community, but I knew the long odds of getting a tenure track position. Now joining academia not only seemed unobtainable but also undesirable. What was I going to do?

2014

In 2014, I asked a question that changed my life, leading me to meet Jess and become one of Allovue’s first employees. I still can’t quite believe the series of events that conspired to put us in a room together that day, for me to ask a conference panel a question, for her to hand me her card, and for me to know just enough to realize that a once in a lifetime opportunity fell in my lap. I met my future boss, mentor, and a dear friend through a chance encounter 2000 miles from home. During my interview, Jess told me she saw “C-level potential” in me. I didn’t understand what she meant, or what she saw in me that I did not see in myself. I guess she was right, a pattern that continues until today, because…

2015

In 2015 I became the Chief Product Officer. I formally left behind a role defined by data analysis to one defined by product management. I am not sure I knew what product management meant. I’m still figuring that out. That summer, we released our first product, Manage. The night before a major product demo and our “announcing” we were in the market with our first customer, everything was broken. I was shaking I was so nervous. At every moment, it felt like I was about to be more proud of what we had accomplished than of any other thing I have done in my whole career or like we were about to fail in some irrecoverable way and this ride would be over. We got it fixed, it worked, we made our first critical sales, and Jess was able to raise our Series A round that fall.

2016

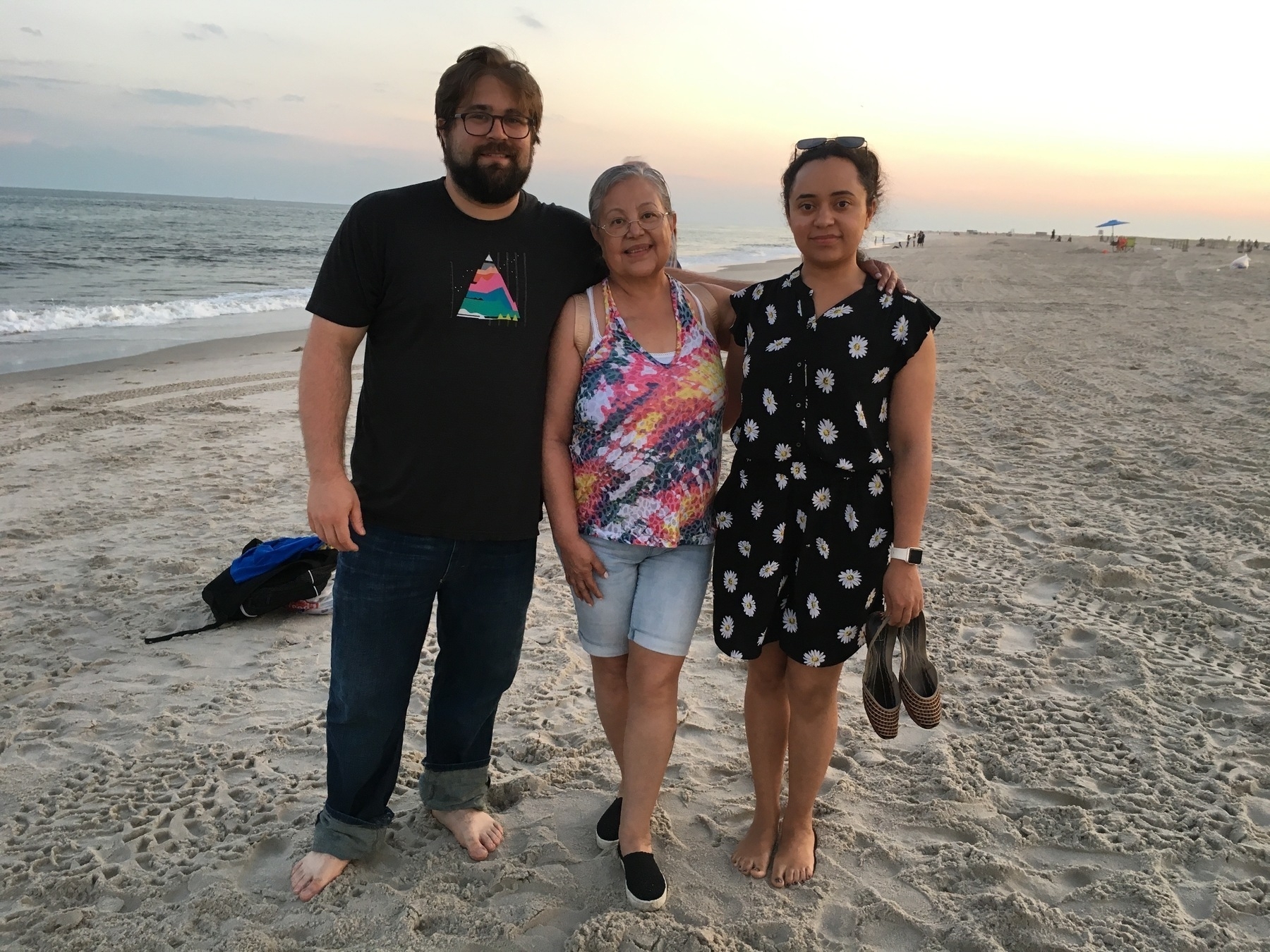

In 2016, a family health issue led us to leave Providence and moving to Baltimore, where Allovue is based. Elsa’s mom moved in with us and brought along with her our second dog, Brandy. Moving was hard. We had just completed redoing our kitchen and bathroom and everything at our condo was just how we liked it. Although Elsa decided to leave her job and was looking for work, the last two years we had started to feel established in our community in Providence. We had solid personal and professional supports. Providence became the home we built together, but it was time to go. In retrospect, I’m glad we left.

2017

In 2017, we lost my grandfather. I turned 30, and I started to take working out more seriously because years of work travel and neglect made me feel bad. I wanted to get back some of the healthy habits I had built a few years prior when Elsa and I both lost a fair amount of weight. Allovue’s CTO Ted left, and I was put in charge of development in addition to design, product management, and data integration. Although we weathered that initial transition well, I think it’s only in 2019 that I truly began to feel comfortable with my new role. We also released our first version of our Budget tool, our second major software product. We bought our house in Hampden, Baltimore. For the first time, we have enough room for family and friends to visit and stay with us and we can host holidays. I love our new home and we’re building a nice life here. Some of my heart remains in Providence, but Baltimore is nudging its way in. I still don’t feel I’ve built the strong emotional ties to Baltimore I had for Providence, but I’d like to get there someday.

2018

In 2018, after a long battle with pancreatic cancer, my Uncle Doug died. I left two weeks later for a wonderful trip with Elsa and visited East Asia for the first time. When I came home, my grandmother had passed away. A month later, my Uncle Marty, who lived with me throughout my childhood, was gone as well. It was the worst two months of my life. The rest of this year is a blur.

2019

In 2019, Allovue doubled in size. We acquired Equiday. We started to put a lot of work into scaling our people and processes and started to work on some still-secret projects that I believe will be the core of our next decade of success. Elsa and I took a wonderful trip to Spain. I failed to keep up with any meaningful physical health routine, but my mental health improved. 2019 is one of the best years I have had in a long time. I rose to meet some major challenges. I traveled more for fun than I have in years. I felt more secure in my friendships, and I felt more secure in my ability to do my job. It took a decade, but at the end of 2019, I’m feeling pretty good about the adult I am still becoming.

A Fitting Finale

At midnight, 12/25 we got engaged after nearly 10 years together.