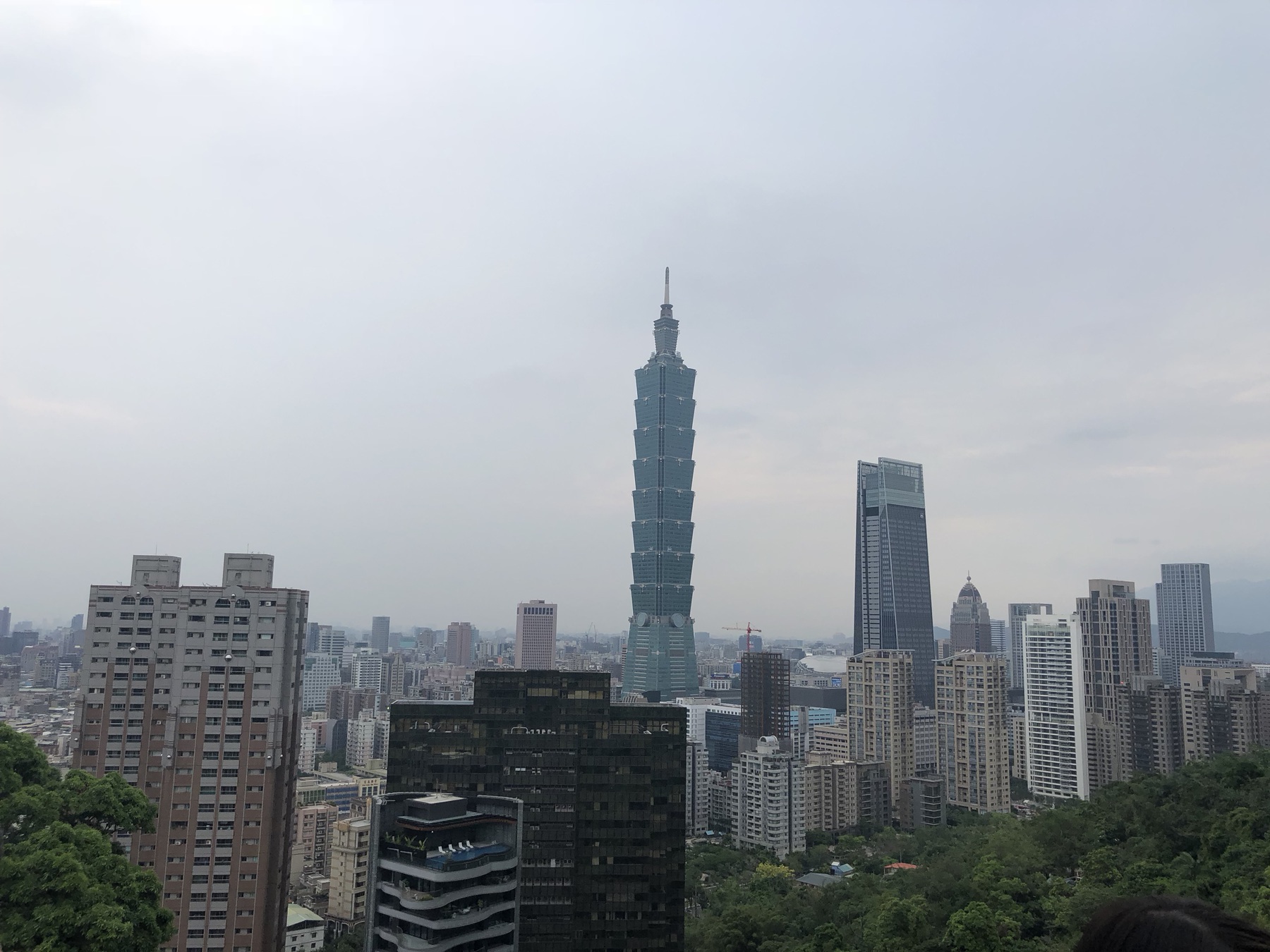

Taipei 101, more walking around the city, a short hike, and total collapse. We missed the night markets because we were just too tired.

About 6 or 7 years ago, Elsa and I visited San Francisco. I think we were there for a conference, but all I remember is wandering the city and that it was the last time I saw our mutual friend Winnie, whom I miss.

Elsa was trying to solve my usual hangry when she pointed out a café across the street and suggested I pop in. She accidentally led me to wander into the attached bookstore, Borderlands Books.

I have long loved sci-fi/fantasy, and it has always made me feel cast out of the mainstream. I never felt different as a nine year old for loving Star Wars, but reading A Wrinkle in Time, The Golden Compass, and The Dark is Rising all before the release of the first Harry Potter book meant I was a true nerd. It didn’t matter that I played sports or that I wasn’t introverted or that I had no social anxiety to speak of. I read a lot, and it was mostly SFF, and that meant I was doomed to the sidelines.

Even in my mid-20s, Borderlands felt affirming.

My friends are not SFF nerds. I don’t have a book club, I don’t go to conventions, I don’t have a fandom, I don’t play TCGs, and I don’t feel connected to the stereotypical nerd community. I still needed Borderlands, or maybe, of course I needed Borderlands.

We don’t see complexity in female stories because we have so little experience imagining it might be there.

This is devastating essay on how we critically consume female art.

I am struggling to think of a single, non-romantic, non-familial, healthy relationship between a man and a woman on screen or in a book that captures the depth and complexity I experience in my life.

I tried to make a point today at an AEFP panel on weighted-student funding that came out all wrong.

We were discussing the differences between school-based autonomy and fiscal equity via WSF. Too often, it was being argued, these two concepts come together. This serves to hold back on achieving equity (potentially) if districts are unwilling/ready to provide greater school-based autonomy (or don’t believe in that model for better resource decision-making).

It’s a good point, especially because autonomy is already largely limited in traditional public school districts due to broader policy decisions around union contracts, state labor law, and restricted fund sources. Regardless of financial allocation model, collectively these restrictions lead to little discretion over how resources are used in schools.

The point I mangled was this: while school-based autonomy is not a necessary feature of WSF, I do think that WSF only has benefits over other allocation models when there is increased discretionary control over resources.

Fiscal equity can be achieved nearly as well with a weighted-staffing model as with weighted-student funding. The WSF translation of resources into dollars associated with students comes with an implicit declaration that various forms of education resources can be used as substitutes. Translating all resources to dollars assumes that quality/quantity trade offs can be made to find more efficient and effective solutions. This includes substituting between personnel and non-personnel resources. Otherwise, what’s the point of translating resources into a common unit (dollars)? If there is no quality/quantity trade off within and across resource classes, then more prescriptive pathways to fiscal equity can be just as effective as WSF. So why bother with the more sweeping policy change to WSF versus producing better staffing models?

What it comes down to it, not tackling teacher compensation methods, teacher assignment, barriers to strategic sourcing of goods and services, etc severely limits the advantages of WSF over other allocation methods.

So yes, WSF doesn’t imply school-based autonomy. But I do believe WSF implies greater autonomy over resource decisions by someone in school or district administration.

I think the internet stopped being fun for me when I was 18 in 2005.

Our family signed up for America Online (and WOW by CompuServe, and MSN, and various other ISPs that gave away hours) starting from about 1996 when I was 9. Putting aside chatrooms and the emergence of messaging services, what I remember most about the internet from my time in middle school through high school were pseudonyms, personal websites that we would now call “blogs” (and their further development with things like LiveJournal), and fan sites.

What was so attractive as a pre-teen and then teenager about the internet was that it was somewhere you can connect with other people in a deeply personal and vulnerable way. You could meet someone with the same interest you thought was obscure. You could share ideas that seemed bizarre, or even radical, and find out that someone else felt the same way, or didn’t, and you learned from that conversation. You could try on personalities and traits that were unlike your own. And because the internet could be anonymous or pseudonymous, and because sites and services and data disappeared, you could do these things without repercussion.

As the world caught on to the internet, there were more and more incentives and requirements to move toward using your “real ID” online. First, and often, as virtue signaling about the seriousness with which you held believes on forums and in chatrooms and on blogs. Second, as a means to ensure that you and only you defined what would be found when increasingly easy and common searches for your name were conducted. And finally, as a strong requirement of the internet services and applications we used which want your real identity because without it you and your data hold little value to them.

I greeted a lot of this with open arms. I remember when I was 18 changing my online pseudonyms all over to my real name. Because I grew up, and the internet grew up. Rather than liberation, anonymity/pseudonymity and acting without repercussion morphed from enabling profound vulnerability to enabling profound harm. It was time for the internet and the real world to come together.

But I miss those early days. It was important to my development as a person to experiment with identity and ideas and to be vulnerable “in public” with other ideas and identities on the web. It was healthy. But it would take a monster amount of work to access the web like that today, and even then, with the internet operating as the largest surveillance apparatus ever constructed, I don’t think I could ever have that naive trust required to be so deeply vulnerable again.

Ideation

At the start of every project, there’s a blinking cursor.

Actually, that’s almost never true for me. If I start staring at a blinking cursor, I’m almost guaranteed to keep looking at a blinking cursor, often for hours. The real work almost always starts weeks or months before I actually type anything. I think it’s easy for folks for whom their ultimate product is a bunch of code or an analysis report to undervalue that our work is creative. Writing a package or doing data analysis is still fundamentally creative work. We’re in the business of using computers to generate evidence to support insights into how things work. If all there was to it was a procedural search through models, then this would all have been automated already.

When I think, “How do I wish I could write my code to solves this problem?” I know that I am getting a great idea for a package. Often, I’m staring at a function I just wrote to make my work easier and start to think “This is still too specific to my work.” I can start to see the steps of generalizing my solution a little bit further. Then I start to see how further generalization of this function will require supporting scaffolding and steps that would have been valuable. I start to think through what other problems exist in data sets unlike my own or future data I expect to work with. And I ask myself again and again, “How do I wish I could write my code to solves this problem?”

Data analysis almost always starts with an existing hypothesis of interest. My guiding thoughts are “What do I need to know to understand this data? What kind of evidence would convince me?” Sometimes the first thoughts are how I would model the data, but most of the time I begin to picture 2-3 data visualizations that would present the main results of my work. Nothing I produce is meant to convince an academic audience or even other data professionals of my results. Everything I make is about delivering value back to the folks who generate the data I use in the first place. I am trying to deliver value back to organizations by using data on their current work to inform future work. So my hypotheses are “What decisions are they making with this data? What decisions are they making without this data that should be informed by it? How can I analyze and present results to influence and improve both of these processes?” The answer to that is rarely a table of model specifications. But even if your audience is one of peer technical experts, I think it’s valuable to start with what someone should learn from your analysis and how can you present that most clearly and convincingly to that audience.

Don’t rush this process. If you don’t know where you’re heading, it’s hard to do a good job getting there. That doesn’t mean that once I do start writing code, I always know exactly what I am going to do. But I find it far easier to design the right data product if I have a few guiding light ideas of what I want to accomplish from the start.

Design

The next step is not writing code, but it may still happen in your code editor of choice. Once I have some concept of where I am headed, I start to write out my ideas for the project in a README.md in a new RStudio project. Now is the time to describe who your work is for and how you expect them to interact with that work. Similar to something like a “project charter”, your README should talk about what the goals are for the project, what form the project will take (a package? an Rmd -> pdf report? a website? a model to be deployed into production for use in this part of the application?), and who the audience is for the end product. If you’re working with collaborators, this is a great way to level-set and build common understanding. If you’re not working with collaborators, this is a great way to articulate the scope of the project and hold yourself accountable to that scope. It also is helpful for communicating to managers, mentors, and others who may eventually interact with your work even if they will be less involved at the inception.

For a package, I would write out the primary functions you expect someone to interact with and how those functions interact with each other. Use your first README to specify that this package will have functions to get data from a source, process that data into a more easy to use format, validate that data prior to analysis, and produce common descriptive statistics and visuals that you’d want to produce before using that data set for something more complex. That’s just an example, but now you have the skeletons for your first functions: fetch, transform, validate, and describe. Maybe each of those functions will need multiple variants. Maybe validate will get folded into a step at fetch. You’re not guaranteed to get this stuff right from the start, but you’re far more likely to design a clear, clean API made with composable functions that each help with one part of the process if you think this through before writing your first function. Like I said earlier, I often think of writing a package when I look at one of my existing functions and realize I can generalize it further. Who among us hasn’t written a monster function that does all of the work of fetch, transform, validate, and describe all at once?

Design Your Data

I always write up a data model at the start of a new project. What are the main data entities I’ll be working with? What properties do I expect they will have? How do I expect them to relate to one another? Even when writing a package, I want to think about “What are the ideal inputs and outputs for this function?”

Importantly, when what I have in mind is a visualization, I actually fake data and get things working in ggplot or highcharter, depending on what the final product will be. Why? I want to make sure the visual is compelling with a fairly realistic set of data. I also want to know how to organize my data to make that visualization easy to achieve. It helps me to define the output of my other work far more clearly.

In many cases, I want to store my data in a database, so I want to start with a simple design of the tables I expect to have, along with validity and referential constraints I want to apply. If I understand what data I will have, how it is related, what are valid values, and how and where I expect the data set to expand, I find it far easier to write useful functions and reproducible work. I think this is perhaps the most unique thing I do and it comes from spending a lot of time thinking about data architectures in general. If I’m analyzing school district data, I want to understand what district level properties and measures I’ll have, what school properties and measures I’ll have, what student property and measures I’ll have, what teacher properties and measures I’ll have, etc. Even if the analysis is coming from or will ultimately produce a single, flattened out, big rectangle of data, I crave normality.

Make Files

So now my README defines a purpose, it talks about how I expect someone to interact with my code or what outputs they should expect from the analysis, and has a description of the data to be used and how it’s organized. Only then do I start to write .R files in my R/ directory. Even then I’m probably not writing code but instead pseudocode outlines of how I want things to work, or fake example data to be used later. I’m not much of a test-driven development person, but the first code I write looks a lot like test data and basic functions that are meeting some test assertions. Here’s some small bit of data, can I pass it into this function and get what I want out? What if I create this failure state? What if I can’t assume column are right?

Writing code is far more fun when I know where I am heading. So that’s how I start my work.

I believe in owning my own space on the web. I have had some form of a blog since LiveJournal, but frequently burn it down to the ground. For a while I’ve maintained a static site, first using Pelican and now Hugo/blogdown. I’ve never been happy with my post frequency, yet I now have over 60,000 tweets. After months of waffling and considering launching my own micro blog using Hugo, I just decided I’d rather pay @manton and get it up and running. If microblogging is the format that keeps me writing, it’s time to not just embrace it, but to support the kind of microblogging that I believe in. Off to figure out how to point micro.json.blog here.

I have some text, but I want the content of that text to be dynamic based on data. This is a case for string interpolation. Lots of languages have the ability to write something like

|

|

|

|

There have been ways to do this in R, but I’ve mostly hated them until glue came along. Using glue in R should look really familiar now:

|

|

Awesome! Now I have a way to make text bend to my bidding using data. But this is pretty simple, and we could have just used something like paste("This is my", pet) and been done with it.

Let me provide a little motivation in the form of data.frames, glue_data, and some purrr.

Pretend we have a field in a database called notes. I want to set the notes for each entity to follow the same pattern, but use other data to fill in the blanks. Like maybe something like this:

|

|

This is a terrible contrived example, but we can imagine displaying this note to someone with different content for each item. Now in most scenarios, the right thing to do for an application is to produce this content dynamically based on what’s in the database, but let’s pretend no one looked far enough ahead to store this data or like notes can serve lots of different purposes using different data. So there is no place for the application to find end_date, price_change, or new_price in its database. Instead, this was something prepared by sales in Excel yesterday and they want these notes added to all items to warn their customers.

Here’s how to take a table that has item_id, end_date, price_change, and new_price as columns and turn it into a table with item_id, and notes as columns, with your properly formatted note for each item to be updated in a database.

|

|

What’s going on here? First, I want to apply my glue technique to rows of a data.frame,

so I split the data into a list using item_id as the identifier. That’s because at the end of all this I want to preserve that id to match back up in a database. 1 The function glue_data works like glue, but it accepts things that are “listish” as it’s first argument (like data.frames and named lists). So with handy map over my newly created list of “listish” data, I create a named list with the text I wanted to generate. I then use a base R function that’s new to me stack, which will take a list and make each element a row in a data.frame with ind as the name of the list element and values as the value.

Now I’ve got a nice data.frame, ready to be joined with any table that has item_id so it can have the attached note!

-

You can split on

row.namesif you don’t have a similar identifer and just want to go fromdata.frameto alistof your rows. ↩︎

I have been using ggplot2 for 7 years I think. In all that time, I’ve been frustrated that I can never figure out what order to put my color values in for scale_*_manual. Not only is the order mapping seemingly random to me, I know that sometimes if I change something about how I’m treating the data, the order switches up.

Countless hours could have been saved if I knew that this one, in hindsight, obvious thing was possible.

Whenever using scale_*_manual, you can directly reference a color using a character vector and then name your value in the scale_ call like so:

|

|

Obviously this is a toy example, but holy game changer.

Looking back on 2017, there were three major trends in my R code: the end of S4, directly writing to SQL database, and purrr everywhere.

The End of S4

The first package I ever wrote extensively used S4 classes. I wanted to have the security of things like setValidity. I liked the idea of calling new as it felt more like class systems I was familiar with from that one semester of Java in college. S4 felt more grown up than S3, more like it was utilizing the advantages of object oriented programming, and less exotic than R6, which in 2014 felt riskier to build with and teach future employees. Using S4 was a mistake from day one and never led to any advantages in the code I wrote.

So this year, I rewrote that original package. It’s internal (and a core function) at my job so I can’t share too much, but this was a long time coming. Not only did I clean up a lot of code that was just plain bad (in the way all old code is), but I got rid of S4 in favor of S3 or more functional code wherever possible. Our test coverage is far more complete, the code is far easier to extend without duplication, and it looks far more idiomatic to the standard non-BioConductor R user.

What’s the lesson learned here? From a technical perspective, it would be avoid premature optimization and, of course, that everyone can and wants to throw out old code they revist with greater knowledge and context. But I know those things. What drove me to making the wrong decision here was purely imposter syndrome. I was writing code that had to be run unattended on a regular basis as a part of a product in a new job. I didn’t feel up to the task, so I felt working with a new, complex, scary part of R that promised some notion of “safety” would mean I really knew what I was doing. So my takeaway from walking away from S4 is this: start small, build what you know, have confidence you can solve problems one at a time, and trust yourself.

Directly Writing SQL

I use SQL far more than R, but almost entirely as a consumer (e.g. SELECT only). I’ve almost always directly used SQL for my queries into other people’s data, but rarely ventured into the world of INSERT or UPDATE directly, preferring to use interfaces like dbWriteTable. This gets back to imposter syndrome– there’s so little damage that can be done with a SELECT statement, but writing into databases I don’t control means taking on risk and responsiblity.

This year I said fuck it– there’s a whole lot of work and complexity going on that’s entirely related to me not wanting to write INSERT INTO a PostgreSQL has the amazing ON CONFLICT...-based “upserts” now. So I started to write a lot of queries, some of them pretty complex 1. R is a great wrapper language, and it’s database story is getting even better with the new DBI, odbc, and RPostgres packages. Although it’s native table writing support is a little weak, there’s no problem at all just using dbSendStatement with complex queries. I’ve fallen into a pattern I really like of writing temporary tables (with dplyr::copy_to because it’s clean in a pipeline) and then executing complex SQL with dbSendStatement. In the future, I might be inclined to make these database functions, but either way this change has been great. I feel more confident than ever working with databases and R (my two favorite places to be) and I have been able to simplify a whole lot of code that involved passing around text files (and boy do I hate the type inference and other madness that can happen with CSVs. Oy.).

purrr

This is the year that purrr not only clicked, but became my preferred way to write code. Where there was apply, now there was purrr. Everything started to look like a list. I’m still only scratching the surface here, but I love code like this:

|

|

It’s a simple way to run through all of the locations (a data.frame with columns code and name) and render an HTML-based profile of each school (defined by having student enrollment). walk is beautiful, and so is purrr. I mean, who does need to do map(., mutate_if, is.numeric, as.character) 10 times a day?

2018 R Goals

One thing that’s bittersweet is that 2017 is probably the last year in a long time that writing code is the main thing my every day job is about. With increased responsibility and the growth of my employees, I find myself reviewing code a lot more than writing it, and sometimes not even that. With that in mind, I have a few goals for 2018 that I hope will keep the part of me that loves R engaged.

First, I want to start writing command line utilities using R. I know almost nothing beyond Rscript -e or ./script.sh when it comes to writing a CLI. But there are all kinds of tasks I do every day that could be written as small command line scripts. Plus, my favorite part of package authoring is writing interfaces for other people to use. How do I expect someone to want to use R and reason about a problem I’m helping to solve? It’s no wonder that I work on product every day with this interest. So I figure one way to keep engaged in R is to learn how to design command line utilities in R and get good at it. Rather than write R code purely intended to be called and used from R, my R code is going to get an interface this year.

Like every year, I’d like to keep up with this blog. I never do, but this year I had a lot of encouraging signs. I actually got considerable attention for every R-related post (high hundreds of views), so I think it’s time to lean into that. I’m hoping to write one R related post each week. I think the focus will help me have some chance of pulling this off. Since I also want to keep my R chops alive while I move further and further away from day to day programming responsibilities, it should be a two birds with one stone scenario. One major thing I haven’t decided– do I want to submit to r-bloggers? I’m sure it’d be a huge source of traffic, but I find it frustrating to have to click through from my RSS reader of choice when finding things there.

Lastly, I’d like to start to understand the internals of a core package I use every day. I haven’t decided what that’ll be. Maybe it’ll be something really fundamental like dplyr, DBI, or ggplot2. Maybe it’ll be something “simpler”. But I use a lot more R code than I read. And one thing I’ve learned every time I’ve forced myself to dig in is that I understand more R than I thought and also that reading code is one of the best ways to learn more. I want to do at least one deep study that advances my sense of self-R-worth. Maybe I’ll even have to take the time to learn a little C++ and understand how Rccp is being used to change the R world.

Special Thanks

The #rstats world on Twitter has been the only reason I can get on that service anymore. It’s a great and positive place where I learn a ton and I really appreciate feeling like there is a family of nerds out there talking about stuff that I feel like no one should care about. My tweets are mostly stupid musings that come to me and retweeting enraging political stuff in the dumpster fire that is Trump’s America, so I’m always surprised and appreciative that anyone follows me. It’s so refreshing to get away from that and just read #rstats. So thank you for inspiring me and teaching me and being a fun place to be.

-

I let out quite the “fuck yea!” when I got that two-common-table-expression, two joins with one lateral join in an upsert query to work. ↩︎

My latest project at work involves (surprise!) an R package that interacts with a database. For the most part, that’s nothing new for me. Almost all the work I’ve done in R in the last 7 years has interacted with databases in some way. What was new for this project is that the database would not be remote, but instead would be running alongside my code in a linked Docker container.

A quick step back about Docker

Docker is something you use if you want to be cool on Hacker News. But Docker is also a great way to have a reproducible environment to run your code in, from the operating system up. A full review of Docker is beyond the scope of this post (maybe check this out), but I would think of it like this: if you run your code in a Docker container, you can guarantee your code works because you’re creating a reproducible environment that can be spun up anywhere. Think of it like making an R package instead of writing an analysis script. Installing the package means you get all your dependency packages and have confidence the functions contained within will work on different machines. Docker takes that to the next level and includes operating system level dependencies like drivers and network configurations in addition to just the thing your R functions use.

Some challenges with testing in R

Like many folks, I use devtools and testthat extensively when developing packages. I strive for as-near-as-feasible 100% coverage with my tests, and I am constantly hitting Cmd + Shift + T while writing code in RStudio or running devtools::test(). I even use Check in the Build pane in RStudio and goodpractice::gp() to keep me honest even if my code won’t make it to CRAN. But I ran into a few things working with CircleCI running my tests inside of a docker container that pushed me to learn a few critical pieces of information about testing in R.

Achieving exit status 1

Only two ways of running tests (that I can tell) will result in a returning an exit status code of 1 (error in Unix systems) and therefore cause a build to fail in a continuous integration system. Without that exit status, failing tests won’t fail a build, so don’t run devtools::test() and think you’re good to go.

This means using R CMD build . && R CMD check *tar.gz or testthat::test_package($MY_PACKAGE) are your best bet in most cases. I prefer using testthat::test_package() because R CMD check cuts off a ton of useful information about test failures without digging into the *.Rcheck folder. Since I want to see information about test failures directly in my CI tool, this is a pain. Also, although not released yet, because testthat::test_package() supports alternative reporters, I can have jUnit output, which plays very nicely with many CI tools.

Methods for S4

The methods package is not loaded using Rscript -e, so if you use S4 classes make sure you call library(methods); as part of your tests. 1

Environment Variables and R CMD check

When using R CMD check and other functions that call to that program, your environment variables from the OS may not “make it” through to R. That means calls to Sys.getenv() when using devtools::test() might work, but using testthat::test_package() or R CMD check may fail.

This was a big thing I ran into. The way I know the host address and port to talk to in the database container running along side my code is using environment variables. All of my tests that were testing against a test database containers were failing for a while and I couldn’t figure out why. The key content was on this page about R startup.

R CMD check and R CMD build do not always read the standard startup files, but they do always read specific Renviron files. The location of these can be controlled by the environment variables R_CHECK_ENVIRON and R_BUILD_ENVIRON. If these are set their value is used as the path for the Renviron file; otherwise, files ‘~/.R/check.Renviron’ or ‘~/.R/build.Renviron’ or sub-architecture-specific versions are employed.

So it turns out I had to get my environment variables of interest into the R_CHECK_ENVIRON. At first I tried this by using env > ~/.R/check.Renviron but it turns out that docker run runs commands as root, and R doesn’t like that very much. Instead, I had to specify R_CHECK_ENVIRON=some_path and then used env > $R_CHECK_ENVIRON to make sure that my environment variables were available during testing.

In the end, I have everything set up quite nice. Here are some snippets that might help.

circle.yml

At the top I specify my R_CHECK_ENVIRON

|

|

I run my actual tests roughly like so:

|

|

Docker adds critical environment variables to the container when using --link that point to the host and port I can use to find the database container.

run_r_tests.sh

I use a small script that takes care of dumping my environment properly and sets me up to take advantage of test_package()’s reporter option rather than directly writing my commands in line with docker run.

|

|

To be honest, I’m not convinced I need to do either the install() step or library(my_package). Also, you can run R CMD build . && R CMD check *tar.gz instead of using the Rscript line. I am also considering copying the .Rcheck folder to $CIRCLE_ARTIFACTS so that I can download it as desired. To do that, you can just add:

|

|

I hope that some of this information is useful if you’re thinking about mixing R, continuous integration, and Docker. If not, at least when I start searching the internet for this information next time, at least this post will show up and remind me of what I used to know.

-

This is only a problem for my older packages. I’ve long since decided S4 is horrible and not worth it. Just use S3, although R6 looks very attractive. ↩︎

I have not yet spent the time to figure out how to generate a JSON feed in Hugo yet. But I have built an R package to play with JSON feeds. It’s called jsonfeedr, and it’s silly simple.

Maybe I’ll extend this in the future. I hope people will submit PRs to expand it. For now, I was inspired by all the talk about why JSON feed even exists. Working with JSON is fun and easy. Working with XML is not.

Anyway, I figured the guy who registered json.blog should have a package out there working with JSON.

Sometimes, silly small things about code I write just delight me. There are lots of ways to time things in R. 1 Tools like microbenchmark are great for profiling code, but what I do all the time is log how long database queries that are scheduled to run each night are taking.

It is really easy to use calls to Sys.time and difftime when working interactively, but I didn’t want to pepper all of my code with the same log statements all over the place. So instead, I wrote a function.

Almost all of timing is straightforward to even a novice R user. I record what time it is using Sys.time, do a little formatting work to make things look the way I want for reading logs, and pass in an optional message.

The form of timing was easy for me to sketch out: 2

|

|

The thing I needed to learn when I wrote timing a few years back was how to fill in STUFF and # Call my function here.

Did you know that you can pass a function as an argument in another function in R? I had been using *apply with its FUN argument all over the place, but never really thought about it until I wrote timing. Of course in R you can pass a function name, and I even know how to pass arguments to that function– just like apply, just declare a function with the magical ... and pass that along to the fucntion being passed in.

So from there, it was clear to see how I’d want my function declartion to look. It would definitely have the form function(f, ..., msg = ''), where f was some function and ... were the arguments for that function. What I didn’t know was how to properly call that function. Normally, I’d write something like mean(...), but I don’t know what f is in this case!

As it turns out, the first thing I tried worked, much to my surprise. R actually makes this super easy– you can just write f(...), and f will be replaced with whatever the argument is to f! This just tickles me. It’s stupid elegant to my eyes.

|

|

Now I can monitor the run time of any function by wrapping it in timing. For example:

|

|

And here’s an example of the output from a job that ran this morning:

|

|

-

tictocis new to me, but I’m glad it is. I would have probably never written the code in this post if it existed, and then I would be sad and this blog post wouldn’t exist. ↩︎ -

Yes, I realize that having the calls to

pasteandcatafter settingstart_timetechnically add those calls to the stack of stuff being timed and both of those things could occur after function execution. For my purposes, the timing does not have to be nearly that precise and the timing of those functions will contribute virtually nothing. So I opted for what I think is the clearer style of code as well as ensuring that live monitoring would inform me of what’s currently running. ↩︎

Non-standard evaluation is one of R’s best features, and also one of it’s most perplexing. Recently I have been making good use of wrapr::let to allow me to write reusable functions without a lot of assumptions about my data. For example, let’s say I always want to group_by schools when adding up dollars spent, but that sometimes my data calls what is conceptually a school schools, school, location, cost_center, Loc.Name, etc. What I have been doing is storing a set of parameters in a list that mapped the actual names in my data to consistent names I want to use in my code. Sometimes that comes from using params in an Rmd file. So the top of my file may say something like:

|

|

In my code, I may want to write a chain like

|

|

Only my problem is that school isn’t always school. In this toy case, you could use group_by_(params$school), but it’s pretty easy to run into limitations with the _ functions in dplyr when writing functions.

Using wrapr::let, I can easily use the code above:

|

|

The core of wrapr::let is really scary.

|

|

Basically let is holidng onto the code block contained within it, iterating over the list of key-value pairs that are provided, and then runs a gsub on word boundaries to replace all instances of the list names with their values. Yikes.

This works, I use it all over, but I have never felt confident about it.

The New World of tidyeval

The release of dplyr 0.6 along with tidyeval brings wtih it a ton of features to making programming over dplyr functions far better supported. I am going to read this page by Hadley Wickham at least 100 times. There are all kinds of new goodies (!!! looks amazing).

So how would I re-write the chain above sans let?

|

|

If I understand tidyeval, then this is what’s going on.

symevaluatesschooland makes the result asymbol- and

!!says, roughly “evaluate that symbol now”.

This way with params$school having the value "school_name", sym(school) creates evaulates that to "school_name" and then makes it an unquoted symbol school_name. Then !! tells R “You can evaluate this next thing in place as it is.”

I originally wrote this post trying to understand enquo, but I never got it to work right and it makes no sense to me yet. What’s great is that rlang::sym and rlang::syms with !! and !!! respectively work really well so far. There is definitely less flexibility– with the full on quosure stuff you can have very complex evaluations. But I’m mostly worried about having very generic names for my data so sym and syms seems to work great.

I have been fascinated with assertive programming in R since 2015 1. Tony Fischetti wrote a great blog post to announce assertr 2.0’s release on CRAN that really clarified the package’s design.

UseRs often do crazy things that no sane developer in another language would do. Today I decided to build a way to check foreign key constraints in R to help me learn the assertr package.

What do you mean, foreign key constraints?

Well, in many ways this is an extension of my last post on using purrr::reduce. I have a set of data with codes (like FIPS codes, or user ids, etc) and I want to make sure that all of those codes are “real” codes (as in I have a defintion for that value). So I may have a FIPS code data.frame with fips_code and name as the columns or a user data.frame with columns id, fname, lname, email.

In a database, I might have a foreign key constraint on my table that just has codes so that I could not create a row that uses an id or code value or whatever that did not exist in my lookup table. Of course in R, our data is disconnected and non-relational. New users may exist in my dataset that weren’t there the last time I downloaded the users table, for example.

Ok, so these are just collections of enumerated values

Yup! That’s right! In some ways like R’s beloved factors, I want to have problems when my data contains values that don’t have a corresponding row in another data.frame, just like trying to insert a value into a factor that isn’t an existing level.

assertr anticipates just this, with the in_set helper. This way I can assert that my data is in a defined set of values or get an error.

|

|

Please Don’t stop()

By default, assert raises an error with an incredibly helpful message. It tells you which column the assertion was on, what the assertion was, how many times that assertion failed, and then returns the column index and value of the failed cases.

Even better, assert has an argument for error_fun, which, combined with some built in functions, can allow for all kinds of fun behavior when an assertion fails. What if, for example, I actually want to collect that error message for later and not have a hard stop if an assertion failed?

By using error_append, assert will return the original data.frame when there’s a failure with a special attribute called assertr_errors that can be accessed later with all the information about failed assertions.

|

|

(Ok I cheated there folks. I used verify, a new function from assertr and a bunch of magrittr pipes like %<>%)

Enough with the toy examples

Ok, so here’s the code I wrote today. This started as a huge mess I ended up turning into two functions. First is_valid_fk provides a straight forward way to get TRUE or FALSE on whether or not all of your codes/ids exist in a lookup data.frame.

|

|

The first argument data is your data.frame, the second argument key is the foreign key column in data, and values are all valide values for key. Defaulting the error_fun and success_fun to *_logical means a single boolean is the expected response.

But I don’t really want to do these one column at a time. I want to check if all of the foreign keys in a table are good to go. I also don’t want a boolean, I want to get back all the errors in a useable format. So I wrote all_valid_fk.

Let’s take it one bit at a time.

|

|

datais thedata.framewe’re checking foreign keys in.fk_listis a list ofdata.frames. Each element is named for thekeythat it looks up; eachdata.framecontains the valid values for thatkeynamed…id, the name of the column in eachdata.framein the listfk_listthat corresponds to the validkeys.

|

|

Right away, I want to know if my data has all the values my fk_list says it should. I have to do some do.call magic because has_all_names wants something like has_all_names('this', 'that', 'the_other') not has_all_names(c('this', 'that', 'the_other').

The next part is where the magic happens.

|

|

Using map, I am able to call is_valid_fk on each of the columns in data that have a corresponding lookup table in fk_list. The valid values are fk_list[[.x]][[id]], where .x is the name of the data.frame in fk_list (which corresponds to the name of the code we’re looking up in data and exists for sure, thanks to that verify call) and id is the name of the key in that data.frame as stated earlier. I’ve replaced error_fun and success_fun so that the code does not exist map as soon there are any problems. Instead, the data is returned for each assertion with the error attribute if one exists. 2 Immediately, map is called on the resulting list of data.frames to collect the assertr_errors, which are reduced using append into a flattened list.

If there are no errors accumulated, accumulated_errors is NULL, and the function exits early.

|

|

I could have stopped here and returned all the messages in accumulated_errors. But I don’t like all that text, I want something neater to work with later. The structure I decided on was a list of data.frames, with each element named for the column with the failed foreign key assertion and the contents being the index and value that failed the constraint.

By calling str on data.frames returned by assertion, I was able to see that the index and value tables printed in the failed assert messages are contained in error_df. So next I extract each of those data.frames into a single list.

|

|

I’m almost done. I have no way of identifying which column created each of those error_df in reporter. So to name each element based on the column that failed the foreign key contraint, I have to extract data from the message attribute. Here’s what I came up with.

|

|

So let’s create some fake data and run all_valid_fk to see the results:

|

|

Beautiful!

And here’s all_valid_fk in one big chunk.

|

|

My thanks to Jonathan Carroll who was kind enough to read this post closely and actually tried to run the code. As a result, I’ve fixed a couple of typos and now have an improved regex pattern above.

-

I appear to have forgotten to build link post types into my Hugo blog, so the missing link from that post is here. ↩︎

-

I am a little concerned about memory here. Eight assertions would mean, at least briefly, eight copies of the same

data.framecopied here without the need for that actual data. There is probably a better way. ↩︎